Quakers, the Quick and the Dead

- Jul 12, 2020

- 11 min read

Updated: Apr 8, 2022

A background to the Society of Friends (Quakers)

In the 16th and 17th centuries Hull, like many other towns, was a place of some religious turbulence. The ‘national church’ spawned by Henry VIII and inherited by his daughter Elizabeth 1st was put under strain by the subsequent Catholic Kings, James 1st and high Church Charles 1st, the latter being beheaded for his troubles.

An essential problem for James was that of governing three countries with differing ‘religious backgrounds’ and this sowed the nettle seeds which later Charles and Cromwell had to grasp through the prosecution of the Civil Wars. Initially Charles threw himself into fighting Catholicism though Puritans believed there was a ‘royal plot’ to restore this faith to Britain. The puritanical Oliver Cromwell abolished the monarchy by executing Charles 1st in 1649 and established the Commonwealth.

Charles 1st. After an original by van Dyck

His abolition of the Anglican Church and his autocratic rule eventually led to the Restoration of the Monarchy by the recall of Charles II, the son of the executed Charles I. Although Charles II had Catholic leanings he enacted laws to uphold the Church of England though on his deathbed he converted to Catholicism. When his brother James II came to the throne he unfortunately caused religious dissent as he tried to emancipate the Catholics thereby infuriating the conservative Anglicans. The fact that he had an heir frightened the establishment further who thought a Catholic lineage was about to develop so William of Orange, a Protestant from the Netherlands, who was married to Mary, James’ II sister, was called to regal duties in Britain. William III, was their son and his gilded statue sits on horse back in Hull’s Market Place.

Statue of King William III (King William of Orange 'Our Great Deliverer') was erected in 1734 in the centre of Market Place. Locally known as 'King Billy' it was designed by Peter Scheemaker and paid for by public subscription. It cost £785 at the time. (Photo Chris Coulson)

A Friends Meeting in Hull was initiated by Richard Emmerson and John Holmes who were influenced by the East Riding preaching of William Dewsbury. The establishment of the Meeting was given a boost by the visits of George Fox in 1652 (after he’d slept the previous night under a haystack), 1658 and 1666. The Meeting was established about 1660. As was their fate the Quakers were soon persecuted particularly by officers of Hull's Garrison and meetings were broken up and people snatched from the street as well as, incredibly, from their own houses. In 1660 six Quakers were imprisoned on return from their expulsion from Hull but following the Act of Tolerance in 1689 the group were left alone to worship as they pleased.

The Hull Meeting covered the old town, Newland and Marfleet though another Meeting was convened at Sutton from about 1665. This Meeting actually post dates the ‘Sutton’ Quaker burial ground which was in use from 1659 though seemingly was only recognised as Quaker in 1672. Originally in the parish of Sutton it now lies between Hodgson St. and Spyvee St and is known as the Hodgson St burial ground. The first burial was Ellen Lilforth in 1659.

The land for this burial ground was previously owned by Anthony Wells. Anthony Wells first wife, Elizabeth, may have been buried there in 1676 but her stone was moved to the Spring Bank Quaker Burial Ground along with four others. Although there were other Quaker burial grounds around Hull there are now only two recognisable ones remaining.

The head stone of Elizabeth Wells, who died in 1676, was the first wife of Anthony Wells (a Hull merchant).She could have been buried in the Hodgson Street Quaker Burial Ground but more likely in Qwstwick in Holderness. The stone was moved in the 1950s from the Spyvee St BG to the Hull General Cemetery Quaker burial ground where it was refound and excavated by Chris Coulson in 2012. (Photo Chris Coulson)

The inscription on Elizabeth Well's head stone. Probably the oldest in the area (Chris Coulson's resources)

All but five head stones disappeared from the Hodgson Street. These were set in a brick structure in the burial ground. These five stones are now in the Hull General Cemetery Quaker site.

The remaining five head stones in the Hodgson Street burial ground were placed on the face of a brick plinth at the southern end of the plot. The Hull Daily Mail photo shows the stones being removed'

When the 'Hodgeson St' burial ground was developed in the parish of Sutton, Hull was still a walled town surrounded by countryside so this burial ground would initially have been in a rural setting. The bodies of early Hull Quakers would have be taken from the Lowgate Meeting House (est 1672) through the north town wall gate and over the River Hull at North Bridge. This bridge was not the first bridge over the River Hull which was built by Henry VIII in 1543 but the second bridge built in 1670. Prior to 1543 people crossed the river by ferry at Stoneferry a few hundred yards to the north. Up to the late 1700s the Quaker burial ground was not really enclosed although factories (flax, cotton and seeds mills) and houses were springing up in the area as the industrial development continued. The burial ground did become surrounded by houses and industrial buildings especially after the north walls of Hull were removed for the development of the Town Dock (later Queens Dock now Queens Gardens) in 1778, at the time the biggest dock in England.

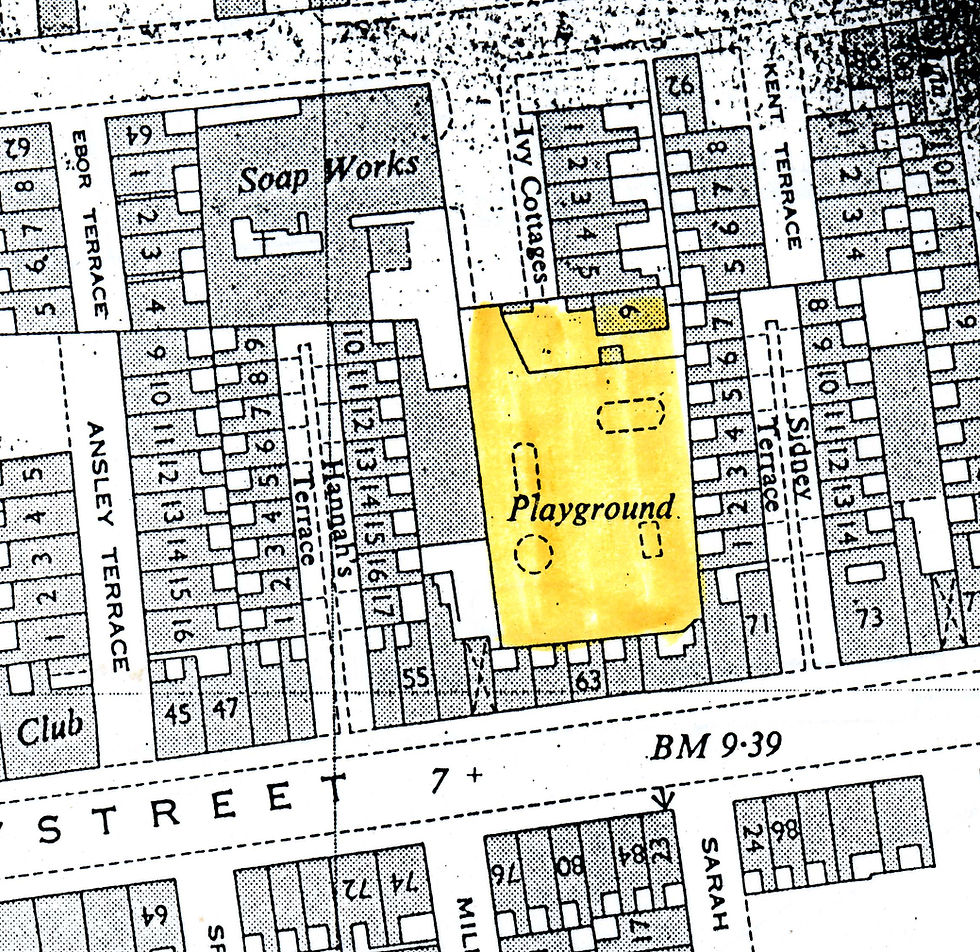

Hodgson Street burial ground when it was a playground. The entrance at the top leads into Hodgson Street.

Hodgeson Street Quaker Burial Ground as a play ground. The date in the top right are the dates of the burial ground

The burial ground was closed in 1858 though only a few years ago some plaques were still attached to the walls of the adjacent buildings. In 1927 it became a children’s playground when still surrounded by houses on three sides and a factory on the fourth. It is currently surrounded on three sides by industrial sites with the only entrance, though not the original one, from Spyvee Street where small terraced houses once stood. The original entrance from Hodgson Street is blocked off now and has been incorporated in one of the adjoining businesses. The plot, is currently 35m x 23.4m (0.2 acre). Nothing remains of the stones marking the burials and the area is it now grassed over. There are Google Earth photographs in which the positions of the graves can just be made out.

At the top of photo is Hodgson Street. The burial ground is now grassed over and enclosed by factories on three sides. The original entrance was the gap between the buildings at the top. Spyvee Street runs across the lower side of the photo. (Courtesy Google Earth)

A more recent Quaker Burial Ground lies within the old General Cemetery on Spring Bank. This cemetery, of 22 acres, was formed by the Hull General Cemetery Company in 1846 in part from farm land under the 'ownership' of Francis Pickwell (14.7 acres) and John Richardson (8.7 acres). The cemeteries opening in 1847 was fortuitous for Hull as from July – Sept 1849, one thousand eight hundred and sixty people, 1 in 43 of Hulls’ population, died in a great Cholera outbreak. As the church yards soon became full seven hundred of the victims were buried in the General Cemetery in a mass grave which is marked by a monument on the cemetery’s northern boundary.

Quaker burial grounds

Quite often Quaker burial grounds were parts of farms or people's gardens but with time they were donated or came under the jurisdiction of the local Meeting.The Book of Discipline sets out the tenets of Quaker beliefs the overriding one being simplicity and that the ground is Gods so there is no reason to consecrate it to be buried in it nor is there a need to use a formulaic funeral service. In general Quaker head stones tend to be plain with little if any ornamentation but there are differences between them because of the overseeing Meetings.

In Ackworth in the West Riding the stones are flat and laid flat on the ground as exemplified by that of Constance Reckitt, the sister of James Reckitt, the industrialist, whose father, Isac, came from Norwich to Hull to make starch.

Constance Reckitt died just before Christmas 1847. It was quite the norm for children away at school to remain in the local village between terms which is why Constance died at Ackworth (Quaker) School and is buried locally. (Photo Alan Rothwell)

Springbank Burial Ground. In 1855 the Quakers took a 999 year lease for £100 on a plot in the General Cemetery. This plot is currently 50.7 m x 18.3 m. (0.23 acre) though a strip of land on the eastern side was donated for a path. Burials commenced here in 1855 initially starting at the southern end of the eastern most row and in the first year of the plot being opened there were three burials the first being Mary Ann Heward who on died on the 23rd June 1855 and was buried on June 28th.

Although the General Cemetery was closed in 1971 burials in the Quaker plot continued until 1974 with the burial of Philip Dent Priestman. This late burial is presumably why his grave does not conform to the others.

The burial ground presently contains 85 graves and some 140 official burials (including cremations) and two unrecorded cremations. What appear as gaps between graves could be burials but could be plots not eventually taken up. Quite frequently you were burried in a Quaker plot where you died. In the Spring Bank Quaker burial plot the head stones are sloping tablets with stone grave surrounds. Notable graves are Isac Reckitt, James Reckitt (his son) and William Priestman the engineer who is famous for the heavy oil engine he developed. There are other well known Quaker families represented here.

Spring Bank Quaker Burial Ground (Photo Chris Coulson)

The Hodgson Street burial ground had flat tablets laid on the ground but on the map of the burials a vault is shown. This unusual grave could have been a brick lined hole in which several bodies were laid. The stone of Elizabeth Wells dated 1672 is probably one of the earliest stones in the area was moved from here to Spring Bank West but may have originated in Owstwick, in Holderness. It is on display at the Quaker burial ground in the Hull General Cemetery on Spring Bank (west).

Hodgson Street Burial Ground (Photo Chris Coulson)

The burial ground in Darlington is again different in that the stones are vertical and in some cases have details of the life of the person buried there. This is generally unusual in Quaker burial plots. In 1717 the stones at Darlington were removed as being 'vain' but in 1830 simple flat stones were introduced and in 1850 upright stones were allowed.

Darlington Quaker Burial Ground (Photo Chris Coulson)

Differences between the two Hull burial grounds

To understand any possible differences between theses two burial grounds, Hodgson St and ‘Spring Bank’ (in Hull General Cemetery) it is useful to recap on a little of their history and the history of Hull.

Initially from at least 1665. Hodgson Street burial ground was associated with the Quaker Meeting in the parish of Sutton. At this time Sutton was a small, rather ‘distant’ village to the north east of Hull and would remain so for over another 100 years. The Sutton Meeting closed in 1685 after moving first to Swine and then to Ganstead, some of the residual Friends eventually joining the Hull meeting. The fact that the Hodgson Street Burial Ground was well away from Hull is testament to the size of the town in the 1600s. The problem of reaching graveyards and the need for ‘decent’ roads was high-lighted by the decree of Edward 1st in the 14th century who noted that some better roads were needed around Hull as reaching the grave yard in Hessle in winter was nigh impossible. So, in the Hodgson St. plot we have two extreme periods of burial, one when it was a totally rural cemetery and the other when it was part of Hull and increasingly surrounded by buildings and indeed squalor. On the other hand the Quaker burial ground in the Hull General Cemetery always was urban and served the west Hull Quakers in an altogether more wealthy part of town. It is said that in UK towns and cities the 'posher' areas are on the west side as the prevailing winds blow their pollution eastward!

Fig1 Shows the years when the two populations were born.

The Hodgson Street and Spring Bank Quakers were born at a similar time to each other and so lived through the same initial years, only the locations and conditions of where they lived differed.

Fig 2. Shows the age at death of Quakers buried at ether Hodgson Street or Spring Bank burial grounds

There is a significant difference between the age of death of the population of the Hodgson Street burial ground (18.3 years old)) and the Spring Bank burial ground (64.3 years old). It seems that these two populations had very differing life lengths although they lived initially through similar years. Was one hit by a catastrophic illness or where there other reasons?

Certainly the data indicates that death rates were higher with bigger variations around the Hodgson Street area than around the west Hull burial ground. (Fig 3). However, it is assumed that people buried in the Spring Bank plot lived in west Hull while those in Hodgson Street lived in that area. This seems a resonable assumption.

Fig 3. Deaths per year of the two populations, Hodgson street and Spring Bank over the same time period

The above data shows that in the 'Hodgson Street' area there are greater fluctuations in death rates among Quakers each year in than in 'Spring bank' (west Hull) and the death rate is also higher.

Fig 4. The age at death in relation to when a person was born (Hodgson Street).

The Hodgson Street area Fig 4 (blue rhomboids) shows that the later a person was born in the 1700 -1800s the shorter was their life span was. A person born around 1770, when the population would have been mainly rural, lived to the age of about 55. After this time the length of life declined. Could this be the result of the building of the town dock and the expansion of the population along the river Hull leading to poor living conditions. A person born about 1840 had a much shorter life span. This is different from the Springbank burial ground in west Hull (red squares) where the scatter of death ages is obviously different to the Hodgson Street deaths. In the Spring bank data there is a period when life length decline rapidly and this coincides quite well with the two Cholera outbreaks in Hull.

The question arises what are the factors involved in these differences between the Hodgson Street and Springbank burial grounds?

Figure 5. The table above suggests some reasons for the poorer life lengths in the Hodgson Street burial ground compared to the Springbank burial ground.

Certainly the standard of living in Hodgson Street area (the Groves) was poor. Over crowding in small substandard houses was common. I have uncovered a case were 27 people co-habited a single small property. Water was taken from the river Hull with its numerous pathogens and a sick person would transfer many of these more easily in crowded conditions. Toilet facilitates were poor or none existent and human excrement had to be usually carried through the 'kitchen' to the street for disposal. Some times if the people who collected it were late it was left in piles at the end of the road until next day. There is a case where a 'butcher' was found using his outside privy to 'dress' his meat. There was a lack of medical care and it has been suggested that 'childrens death clubs', where parents insured their child's burial could have led to less care for the child when alive!

It is probable that research on municipal cemeteries would show a similar trend. I have always noticed that the age of death of people reported in the Times newspaper seems greater than those in the local paper!

Chris Coulson

Sept 2019.

Comments